The Emergence of Female Roles and Its Impact on Early Life

As evolutionary history progressed, environmental pressures intensified. Frequent extinction events, habitat challenges, and resource scarcity drastically shaped the survival mechanisms of early life forms. In this context, female roles emerged—a pivotal change in reproductive strategy that significantly altered social structures, mating behaviours, and even population stability. This chapter explores how natural selection favoured female differentiation due to dwindling populations of early male-pregnant organisms and passive males, ultimately leading to mixed reproductive strategies. Yet, the shift to male-female dynamics was not without cost. Disease proliferation, competition for territory, and social disruption ensued, complicating life’s adaptive journey.

BIOLOGY

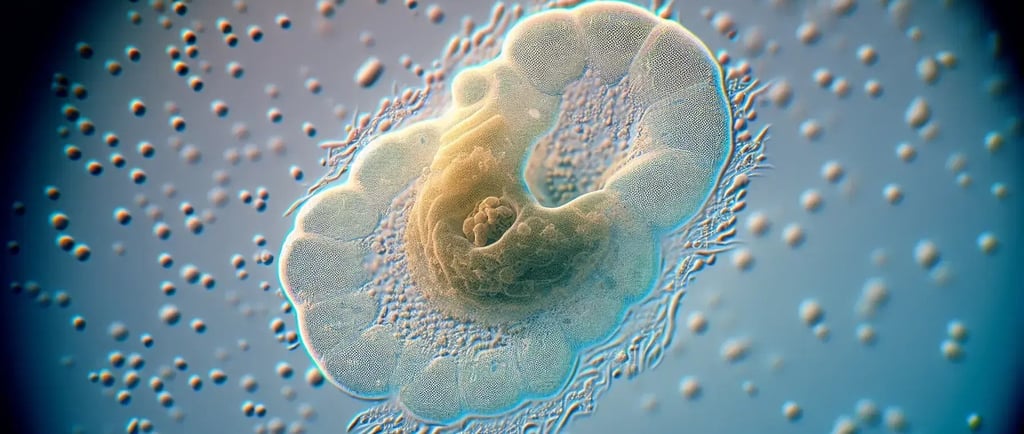

Throughout the Permian, Triassic, and even early Jurassic periods, life on Earth faced severe environmental pressures that led to several mass extinctions. These catastrophic events caused widespread loss of biodiversity, reducing populations and threatening the survival of many male-only species that carried offspring. With high male mortality rates, the evolutionary mechanism to increase genetic diversity and adaptability became crucial.

Baby-carrying male organisms, vulnerable due to their reproductive roles, were heavily impacted during these extinction events. As these males became scarce, natural selection began favouring genetic mutations that encouraged the development of a distinct female role, allowing offspring to be nurtured outside the male body. This shift, however, had consequences, as males had evolved efficient methods of reproduction that didn’t require the complex competition seen in mixed-gender systems. Male-male relationships had previously maintained stable population levels without the added pressures of mate competition and disease spread.

With reduced male populations unable to sustain pre-existing male-only reproductive practices, natural selection began favouring the differentiation of female roles. This adaptation provided a new, though complex, reproductive method. By establishing females as egg carriers, genetic diversity increased, enabling species to withstand environmental challenges better. However, this change introduced dynamics that would eventually complicate population stability and social cohesion among early species.

Introducing females allowed for faster population recovery and improved genetic mixing, yet it disrupted the simplicity of male-only reproduction. Competition for mates intensified, leading to aggression and territorial disputes that had been minimal in male-male societies. The newfound female presence, while adaptive, began to destabilise certain species and their populations. Where males had once cooperated within hierarchies to support reproduction, female introduction disrupted these dynamics, contributing to intergroup conflict and competition.

The shift to male-female pairing presented unforeseen challenges, leading to an increase in disease transmission, resource conflicts, and social discord. These complications arose primarily from the need for larger territories, heightened competition for mates, and the physical separation of parental roles.

Females often sought multiple partners to enhance offspring genetic variety, leading to fierce competition among males. In species where hierarchical male bonds had ensured reproductive order, female presence spurred intense territorial battles, often resulting in injury and sometimes death. These conflicts destabilised formerly cooperative groups, placing strain on populations that were already struggling to adapt to the new reproductive system.

In some species, the shift to a mixed-gender system and the subsequent increase in female numbers led to instability and, eventually, extinction. Overpopulation of females, combined with new social stresses, contributed to the decline of several early species.

Certain species, unable to cope with the social and health challenges brought by female roles, saw their populations plummet. Examples include early Permian-era tetrapods like Diadectes and Seymouria, which were outcompeted by species better adapted to the new reproductive paradigm. Similarly, some therapsids, early relatives of mammals, struggled with the increased demands of mixed-gender social structures. For these species, male-male reproduction had been sufficient for population maintenance, but female presence brought new reproductive pressures that they could not adapt to, ultimately leading to their extinction.

The introduction of female roles, while evolutionary advantageous in some respects, also brought challenges that disrupted previously stable male-male reproductive societies. Disease spread, territorial conflicts, and increased competition created instability among early life forms, leading to the extinction of species unable to adapt to the new reproductive structure. However, as evolution progressed, certain modern animals maintained strong male-male bonds, often proving more stable and beneficial than male-female interactions.

In the next chapter, we will explore how homosexual bonds remain prevalent in various animal species today. Additionally, some passive males in these species still retain genetic traces enabling them to conceive, despite the introduction of distinct female roles. This chapter will also discuss specific cases of male pregnancy observed in fish, birds like penguins, certain rare mammals, and unique human societies where male-to-male reproduction maintains a prominent cultural or biological role.