Origins of Male-Male Relationships in Early Life Forms: A Scientific Exploration

The evolutionary history of reproductive relationships reveals insights into early life forms, particularly concerning male-male interactions. This paper examines how these interactions, devoid of females, were foundational to reproductive strategies in some of the earliest known organisms. By tracing significant geological periods and milestones, from unicellular life to early vertebrates and synapsids, we explore how reproduction and social structures developed through male-male interactions before the introduction of distinct female roles. This analysis shows that before life diversified into male-female pairings, male-only reproductive relationships played a crucial role in survival and adaptation.

BIOLOGY

Life’s journey began approximately 4.6 billion years ago during the Precambrian era. Earth’s atmosphere was inhospitable, with intense volcanic activity, high temperatures, and minimal oxygen levels. Early life emerged as single-celled organisms, lacking sex differentiation but beginning to explore rudimentary methods of genetic exchange essential for survival. This was a period of primarily male-male reproductive interaction, as early organisms did not yet exhibit distinct female roles or require them for reproduction.

Early life forms, such as prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), relied on asexual reproduction—binary fission and budding were the primary methods, producing genetically identical offspring without the need for a separate female counterpart. Over time, however, primitive forms of sexual reproduction appeared, specifically in eukaryotes around 2 billion years ago. While sexual reproduction was not yet male-female, some organisms engaged in genetic recombination with other males, facilitating survival and genetic diversity.

The lack of female differentiation in this era meant that male-male interactions were the basis for all genetic exchange. Evidence of conjugation among eukaryotes—an early gene-exchanging behaviour—suggests that early forms of temporary bonding for reproduction were inherently male-male. These relationships set the stage for later reproductive strategies and marked the beginnings of reproductive partnerships, though distinct female roles were still millions of years away.

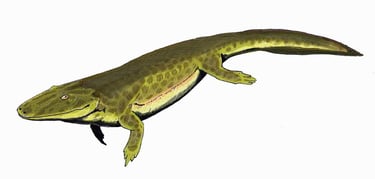

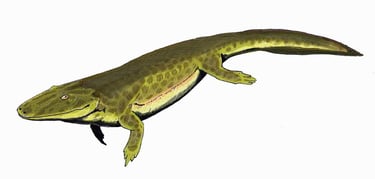

During the Carboniferous period (approximately 358 to 298 million years ago), the emergence of amniotes—a group of tetrapods with egg-laying adaptations—marked a significant evolutionary milestone. These early amniotes, lacking females, laid eggs through male-male interactions in complex social structures. Representative amniote species like Hylonomus, Palaeothyris, and Captorhinus illustrate that male-only reproductive roles dominated this period, long before female roles appeared.

Male-male reproductive hierarchies likely emerged as dominant male amniotes secured primary roles in genetic exchange. Early hierarchical behaviours and alliances among males enabled dominant males to monopolise reproductive functions, while subordinate males participated in supportive roles within groups. These interactions allowed amniotes to thrive in terrestrial environments, where male-male relationships were essential for survival and reproductive success.

The adaptation of laying eggs without females points to a stage of evolution where male-exclusive relationships formed the basis of all social and reproductive activity. Dominant males, by controlling access to resources, reinforced social order, ensuring group stability. This male-only system laid the foundation for social structures that would eventually evolve toward male-female pairings once environmental pressures favoured the inclusion of females.

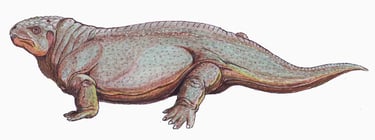

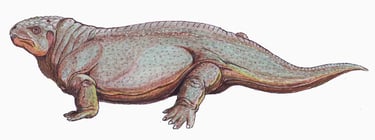

The Permian period (298 to 251 million years ago) saw the rise of synapsids, ancient relatives of mammals that would later give rise to more complex vertebrates. Notable synapsid species such as Dimetrodon, Sphenacodon, and Edaphosaurus exhibited male-male reproductive behaviours in a world yet to see female differentiation. The climate’s extreme fluctuations led these creatures to develop unique male-only reproductive strategies, fostering male alliances and dominant-subordinate hierarchies essential for survival.

Early synapsid societies relied heavily on male-male cooperation. These animals were highly territorial, with dominant males taking leading reproductive roles while forming alliances with other males within their groups. Without females, these synapsid males exhibited a social structure similar to that seen in later mammalian hierarchies, where male dominance determined reproductive privilege.

Male-male reproductive behaviours likely enhanced the group’s resilience, allowing for better survival rates by reducing competition and promoting stable social interactions. The lack of females meant that males in synapsid groups formed lasting alliances, with relationships reinforcing cooperation over reproduction. These early alliances demonstrate the foundational role of male-male relationships in fostering reproductive and social success.

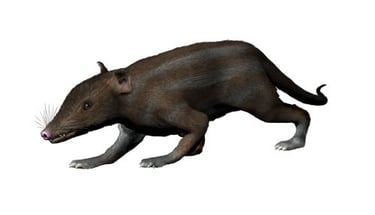

During the Triassic period (251 to 201 million years ago), following a massive extinction event, synapsids that survived diversified, giving rise to early mammalian relatives. Species such as Thrinaxodon, Oligokyphus, and Cynognathus displayed behaviours reminiscent of early mammals, though female roles were still absent. These early relatives continued the tradition of male-male interactions, with dominant males holding primary reproductive roles within group structures.

The lack of females in these early mammalian relatives encouraged a high degree of reproductive flexibility and social bonds between males. Fossils suggest these creatures lived in groups, possibly to increase protection from predators, relying on strong male-male alliances to ensure the success and stability of their communities. Male-male bonding fostered cooperation and trust, and these interactions may have supported the survival of offspring within the group, demonstrating an early model of social and reproductive care systems.

Without females, these early mammalian relatives used male-only structures to foster group cohesion and maintain territorial dominance. Subordinate males provided support roles, helping to stabilise the group. These early behaviours show the adaptability of male-only societies in primitive mammals and highlight how male-male relationships were essential in shaping early social frameworks.

The dominance of male-male relationships in the early vertebrate lineage points to an evolutionary strategy where reproductive success was driven by cooperative male structures. From social hierarchies to resource sharing, male-male alliances allowed vertebrates to thrive in an era before female roles had emerged. This adaptation can be observed in modern animals with strong male-male bonds, such as primates, cetaceans, and certain mammals, where alliances strengthen group survival and cooperation.

In early vertebrates, male bonding provided a reliable reproductive strategy. Such alliances promoted reproductive exclusivity for dominant males and stability for subordinates. These relationships provided the foundations for cooperation and social bonding, which would influence the future dynamics of group living and reproductive structures as female roles developed.

The eventual differentiation of female roles represents a significant evolutionary shift, introduced as genetic variations enabled organisms to adopt egg-laying and nurturing roles. Female roles likely arose due to environmental demands that required reproductive efficiency, genetic diversity, and decline in baby carrying males. This differentiation became critical for adaptation, especially as ecosystems became increasingly complex.

Once the environment required more efficient reproduction strategies, genetic mutations supporting differentiated roles, particularly female roles, arose. These adaptations proved beneficial as life continued to diversify, allowing for the specialisation of male and female roles in reproductive strategies. The introduction of female roles created an emergency back up plan.

This final adaptation to male-female reproductive dynamics transformed early life by establishing roles that allowed for distinct genetic lines. Although male-male relationships provided the basis for social structures, the inclusion of females eventually became the main cause for most species that survived mass extinctions.

The evolutionary history of male-male relationships shows a vital pathway in the reproductive and social structures of early life. From unicellular gene exchanges to complex alliances among early vertebrates and synapsids, these interactions were foundational before female differentiation. Examining these male-male relationships reveals how cooperation, competition, and bonding contributed to the survival of early species. While female roles would eventually emerge, male-male reproductive strategies played an essential role in life’s evolutionary journey. In the next chapter, we will explore the biological factors and genetic mechanisms that led to the eventual establishment of female roles, revolutionising reproductive systems and enabling the diversity of life as we know it.